THE AUTHOR'S CUT

This website is a supplement to Guitar King: Michael Bloomfield's Life in the Blues, a biography of America's first great blues-rock guitarist. Certain passages were necessarily omitted from the book's nearly 800 pages, due to space limitations. But those passages are offered here as a digital appendix.

'GUITAR KING' BONUS PAGES

TWIST PARTY

Playing with Butterfield

1963 | By David Dann, supplemental to Guitar King: Michael Bloomfield's Life in the Blues

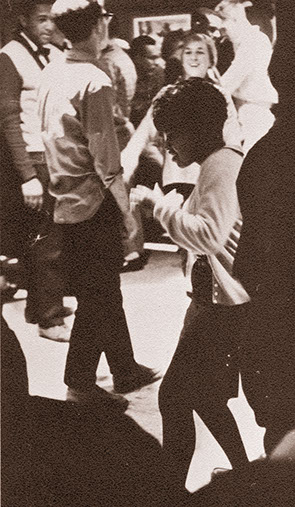

Dancers frolic to live music during one of the Wednesday night Twist Parties. University of Chicago yearbook photoIN HYDE PARK, the mid-week dance parties that had begun two years earlier were now a University of Chicago tradition. Those “twist parties” had grown so large and raucous, with amplified bands providing the music, that the administration had moved them from the New Dorms to one of the big lounges in Ida Noyes Hall, the school’s student center. There, every Wednesday night at 9 p.m., when school was in session, students and friends from the surrounding community would gather to dance to the blues. More often than not, it was Paul Butterfield who was leading the band that provided those blues.

Dancers frolic to live music during one of the Wednesday night Twist Parties. University of Chicago yearbook photoIN HYDE PARK, the mid-week dance parties that had begun two years earlier were now a University of Chicago tradition. Those “twist parties” had grown so large and raucous, with amplified bands providing the music, that the administration had moved them from the New Dorms to one of the big lounges in Ida Noyes Hall, the school’s student center. There, every Wednesday night at 9 p.m., when school was in session, students and friends from the surrounding community would gather to dance to the blues. More often than not, it was Paul Butterfield who was leading the band that provided those blues.

Butterfield had been developing his electric sound in clubs around the South Side and by the fall of 1963 was already playing harmonica with the skill and authority of a Chicago veteran. He had become a regular attraction at the Blue Flame Lounge, a club on 39th Street near Drexel Boulevard, performing nightly as a featured member of Little Smokey Smother’s band. Guitarist Smothers had heard Butterfield playing harp on a stoop in Hyde Park one afternoon and invited him to sit in at the club. That guest appearance turned into a steady gig, with Paul playing to audiences that were amazed to see a white boy blowing harmonica with the dexterity of Big Walter Horton or Junior Wells. A familiar figure around the South Side, Butterfield was known as a gifted player and as someone who fit in easily. Often he would be the only white person in a club, and that club might be in the toughest West Side neighborhood. But Paul was always accepted.

“Black people loved Butterfield,” commented Paul’s friend and occasional musical partner, Nick Gravenites. “He grew up with blacks … he was happy, easy-going, a sweet guy back then.” (1) Though Butterfield had tried a few semesters at the University of Illinois after high school, he soon was spending all his nights in Bronzeville jamming with masters like Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf. He was getting an education in the blues and, because he was such a serious student of the music, he earned the respect those he was learning from and from the black audiences who heard him.

Butterfield was also known on campus as an exciting player. The university’s students flocked to the Wednesday night soirees to hear him play classic blues like Little Walter’s “Everything’s Gonna Be Alright” and “Mellow Down Easy,” or “19 Years Old” by Muddy Waters. Norman Dayron was a fan, too – enough so that he’d recorded Paul in September at one of the university’s other large halls. That session had been a notable one.

“Because I was an instructor and was teaching Humanities 101, I was put in charge of the art gallery in Lexington Hall,” said Dayron. “It had originally been a ladies’ gymnasium and was this huge, resonant room. It had natural reverb because of its high ceiling. I had the key and that’s where I made the very first recordings of Paul.” (2)

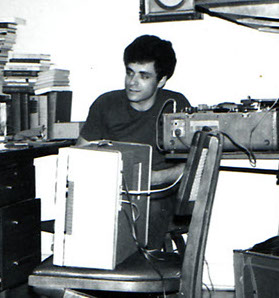

Norman Dayron with his recording equipment in 1963. Photo courtesy Norman DayronNorman had set up his bulky Telefunken tape deck in the gallery late one night, positioning Butterfield in the center of the hall. Paul had brought along Elvin Bishop as his accompanist and they were joined for the session by two other Chicago harp players. One was James Cotton, the gifted blues musician who had gotten his start in the 1950s as Howlin’ Wolf’s harmonica player and had later replaced Little Walter in Muddy Water’s band. The other, William “Billy Boy” Arnold, had done a few gigs for Mike and George Mitchell at the Fickle Pickle, but he had also recorded with Bo Diddley and under his own name for the Vee-Jay label. Dayron wanted to record the five musicians in various combinations, thinking he might interest Pete Welding in using some of the material for a Testament Records release.

Norman Dayron with his recording equipment in 1963. Photo courtesy Norman DayronNorman had set up his bulky Telefunken tape deck in the gallery late one night, positioning Butterfield in the center of the hall. Paul had brought along Elvin Bishop as his accompanist and they were joined for the session by two other Chicago harp players. One was James Cotton, the gifted blues musician who had gotten his start in the 1950s as Howlin’ Wolf’s harmonica player and had later replaced Little Walter in Muddy Water’s band. The other, William “Billy Boy” Arnold, had done a few gigs for Mike and George Mitchell at the Fickle Pickle, but he had also recorded with Bo Diddley and under his own name for the Vee-Jay label. Dayron wanted to record the five musicians in various combinations, thinking he might interest Pete Welding in using some of the material for a Testament Records release.

“Elvin was playing this National resonator guitar, and we recorded a dozen tunes in multiple takes,” said Norman. “One was called ‘3 Harp Boogie’ and it had Paul, Cotton and Billy Boy all playing together. They sounded really great!” (3)

Dayron was so pleased with the results that he decided to capture Butterfield’s electric sound at one of the university’s twist parties. Paul was enthusiastic too, eager to hear how he sounded with the group.

A week after the Lexington Hall session, on Wednesday, October 2, the journeyman audio engineer brought his equipment over to Ida Noyes Hall and set up a couple of microphones out in front of the band while they were finishing up their first set. Because Butterfield sang through his harp mic, using his amplifier as a makeshift PA, Norman placed one mic nearer to Paul’s amp to better capture the vocals. It would be Dayron’s first attempt at recording electrified instruments and drums, and he knew it would be a challenge.

The main hall in the University of Chicago's Ida Noyes student center. University of Chicago photoMike Bloomfield learned of his friend’s plans to capture the twist party on tape and decided to come along and sit in. He brought his beat-up Duo-Sonic to the party along with his amp and, after getting the OK from Paul, positioned himself to one side of the band.

The main hall in the University of Chicago's Ida Noyes student center. University of Chicago photoMike Bloomfield learned of his friend’s plans to capture the twist party on tape and decided to come along and sit in. He brought his beat-up Duo-Sonic to the party along with his amp and, after getting the OK from Paul, positioned himself to one side of the band.

The big room was hot and crowded with revelers. With its polished floor, two-story-high gothic windows, wrought-iron chandeliers and oak-paneled wainscoting, the hall – and its lofty sounding name, the Cloisters Club – was better suited to debutant cotillions than to South Side blues parties. But the music was loud, exciting and rhythmically infectious, and the dancers were eager to blow off steam after the rigors of class work. They came not only from the surrounding dorms but also from the Hyde Park neighborhood and, as a result, the crowd was an integrated one. But no one seemed to notice, and no one seemed to mind paying the ten-cent admission charge, knowing that funds raised were to be spent on buying “beer for the band.” (4)

The Wednesday-night parties provided one of the few times during the week that the sexes could intermingle socially on campus, and they offered students a chance to get to know some of their neighbors. And then there was the music.

Paul Butterfield’s second set started with an improvised instrumental, a shuffle blues. Norman stood to one side of the band, monitoring the volume level on the Telefunken and starting and stopping the recorder in an effort to conserve tape. The band’s sound was big, but it didn’t seem to overwhelm the machine.

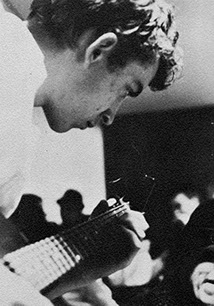

Elvin Bishop performs at a U.C. Twist Party. University of Chicago yearbook photoIn the group, along with Paul and his frequent partner Elvin Bishop, were two African Americans. They were brothers who ran a shoe repair business in Hyde Park and played jazz and rhythm ‘n’ blues after hours for fun. Buddy Wilson, the shop’s owner, was the bass player while Teddy, his younger brother, played drums. They weren’t particularly well-versed in Chicago blues styles, but Teddy could keep a beat and Buddy could follow Paul’s lead.

Elvin Bishop performs at a U.C. Twist Party. University of Chicago yearbook photoIn the group, along with Paul and his frequent partner Elvin Bishop, were two African Americans. They were brothers who ran a shoe repair business in Hyde Park and played jazz and rhythm ‘n’ blues after hours for fun. Buddy Wilson, the shop’s owner, was the bass player while Teddy, his younger brother, played drums. They weren’t particularly well-versed in Chicago blues styles, but Teddy could keep a beat and Buddy could follow Paul’s lead.

Following the set opener, Butterfield went into a version of Sonny Boy Williamson’s current hit, “Help Me.” He began the tune with a solo chorus, his harp evoking the big, swooping sound of a tenor saxophone. The effect was bracing, and it elicited excited cries from the dancers. Elvin and Buddy Wilson played the tune’s powerful riff in unison behind Paul while Teddy Wilson kept a simple beat on his bass and snare drums, punctuating the turnarounds with a flourish of tom-toms and cymbals. Paul’s vocal, though muted by his amp’s treble-less settings, was gutsy and effective. Elvin took a few solo choruses, and his single-string runs showed that in his few years in Chicago he’d come a long way toward mastering elements of the South Side blues idiom. But it was Butterfield’s solos that gave the band its exciting energy. His phrasing and tone didn’t just recreate those of Chicago’s seasoned bluesmen, they constituted a fresh new voice. Paul Butterfield was clearly a gifted musician, and he was unquestionably master of the evening’s festivities.

After several more choruses, “Help Me” came to an abrupt end. As the dancers applauded, Paul turned to Elvin. “What the hey! Elvin? Why’d you end it, man?” he shouted at his guitarist, annoyed that Bishop had misread a cue and brought the tune to a premature conclusion. Elvin grinned sheepishly, but said nothing.

After blowing a few riffs on his harp, Butterfield kicked off the next tune. It was Little Walter’s “Crazy for My Baby.” The piece’s signature stop-time riff punctuated Paul’s vocal:

Every time I lay down to sleep

I dream my baby is kissin’ me

Sweet little girl, you know she’s so fine

I just can’t get her off my mind.

I’m crazy for my baby …

On the first chorus, a second guitar was heard over Elvin’s shuffling bass line. Mike Bloomfield had suddenly joined the quartet. His sound was quite different from Bishop’s – it was twangy, biting and aggressive. Butterfield followed his vocal with two ferocious harp choruses, blowing a single repeated note in triplet rhythm over the rolling shuffle beat and roaring a chord for a full measure to open his second twelve bars. After his second vocal, it was Bloomfield’s turn.

As if taking up a challenge, Bloomfield attacked the beat with his own fusillade of triplets. His playing was fast and clean, accomplished where Bishop’s had been somewhat rudimentary. He toyed with the beat in a cascade of notes, threatening to overwhelm it but never losing it. In his second chorus, Michael dropped down two octaves to a low F in marked contrast to his opening statement. Butterfield was clearly impressed. “Looking good, ha, ha!” he laughed into his microphone.

In a matter of thirty seconds, Bloomfield had established himself as the other solo voice in the room. While it was Paul’s gig, Michael was unquestionably a dominant presence. And it wasn’t only his sound and flashy proficiency that grabbed the dancers’ attention. As Bloomfield soloed, his whole body contorted in response to his lead lines, jerking forward one moment and arcing backward then next. Grimacing wildly as he stretched a string, his expression alternated between intense pain and jubilant elation. His mouth seemed to articulate the phrases as though he himself were the instrument. Michael was a visual as well as aural spectacle, unlike anything the dancers had ever seen.

The tune came to an end to cheers from the gyrating twisters.

As the band readied for the next number, Norman Dayron let the tape run. He didn’t want to miss anything. “What are you doin’, man?” Buddy asked, looking to Butterfield to call the tune. “’What’d I Say’,” came Paul’s reply. Looking at Elvin, he urged, “Go ahead − go ahead!”

Bishop began the Ray Charles song alone, running through a chorus playing the bass line that opens the piece. Butterfield joined in on harmonica midway through the chorus, and then Buddy and Teddy picked up the rhythm, supplying the boogaloo beat. On the second chorus Bloomfield dropped in, leavening the mix with chords and a few fills. At the break between the second and third choruses, Michael recreated Charles’ signature piano lick with studied accuracy. Teddy Wilson played off the guitarist’s energy and brought the band back in with a thunderous roll on his snare.

Michael Bloomfield and Paul Butterfield sitting in at Theresa's in 1964. Norman Dayron photo“That was all Michael’s doing,” said Norman Dayron, listening to the tape many years later. “He got Paul to do that tune. In those days, Butterfield wouldn’t have done something by Ray Charles.” (5)

Michael Bloomfield and Paul Butterfield sitting in at Theresa's in 1964. Norman Dayron photo“That was all Michael’s doing,” said Norman Dayron, listening to the tape many years later. “He got Paul to do that tune. In those days, Butterfield wouldn’t have done something by Ray Charles.” (5)

Mike Bloomfield had learned “What’d I Say” back in 1959 when it was first released on Atlantic. He’d liked it so well that he’d worked up his own bawdy variation of its lyrics to entertain his high school bandmates, and he’d played the tune countless times since then on North Side rock ‘n’ roll gigs. Butterfield knew the song and liked it too, but his preference was for Chicago-style blues. He called it because he knew the dancers loved it and because the beat was more in line with what Teddy Wilson was comfortable playing. He knew too that Bloomfield could add exciting embellishments to the rhythm parts. Skipping the first two verses, Paul came in singing Ray Charles’ third set of lyrics:

Tell your mama, tell your pa

I’m gonna send you back to Arkansas

Oh, yes, now, you don’t do right

You don’t do right, oh yeah!

He followed that with a chorus on harp, filling the break with another of Charles’ licks. After the next round of lyrics, Mike did a break repeating the lick Paul had just played, beginning it on his open E string – the lowest note possible on his Duo-Sonic. Next came the part the dancers were waiting for – the call-and-response.

“Well …” Butterfield moaned as Teddy worked the beat. “Whoa!” replied the audience. “Well.” “Whoa.” “Well – whoa – well – whoa – well, whoa, well, whoa, well, whoa … One more time!” The band worked through several more choruses and another enthusiastic call-and-response break before bringing the tune a close. Teddy Wilson, reluctant to give up the groove, even kept the beat going for a few extra measures.

The twist party band clearly knew “What’d I Say.” Their arrangement was elaborate enough that it had to have been worked out in advance, and the party goers knew to be ready for the call-and-response.

“We had a couple of bands that played other gigs, with different personnel − the Salt and Pepper Shakers and the South Side Olympic Blues Team,” recalled Elvin Bishop. “So it wouldn’t be strange if the tune sounded organized.” (6) Mike Bloomfield had played numerous times at the Wednesday evening gatherings and more than a few of those times he’d sat in with Paul Butterfield’s little band. The harmonica player was a demanding leader and not easily impressed, but the fact that he would do the Ray Charles tune was a testimonial to Bloomfield’s skills.

Still, Paul didn’t really think of Mike as a serious blues player.

“Michael was in rock-and-roll and show bands when he was 16, 17 years old,” Butterfield told an interviewer many years later. “Michael really got interested in blues, like Muddy and those cats, after he’d been playing in rock 'n' roll and show bands. He was never down on the South Side before then. I never saw that cat on the South Side.” (7)

Even though Bloomfield had been going to hear and play blues in Bronzeville since 1958 – nearly as long as Butterfield – there was more than a little truth in the harmonica player’s observation. Michael’s earliest influences came from rock ‘n’ roll, as he himself frequently acknowledged. He prided himself on being able to play the fast, riff-oriented lines of Cliff Gallup and Scotty Moore, and their influence was still very much evident in his electric playing. Despite his enthusiasm for blues masters like B.B. King and T-bone Walker, Bloomfield’s lead that October evening at the Cloisters Club was derived as much from rock as it was from blues.

But it was just that quality – Michael’s ability to draw from both styles and merge them – that made his playing so dynamic, so exciting.

After a few more numbers, the dance began breaking up. The university’s female students were under a strict curfew and dorm doors were locked at midnight, so twist parties couldn’t go much beyond 11:30 p.m. Butterfield rallied his men for one last tune, joking with the crowd. “’Scuse me, ‘scuse me, please. 'Scuse me. I've got to go home! I've got to go home to my baby someday,” he laughed into the microphone. Then he turned to Michael and shouted, “Play on!”

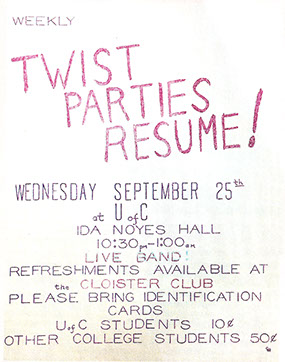

A flyer a UC Twist Party at Ida Noyes Hall. Author's collectionBloomfield jumped into the tune with a repeated lick reminiscent of Otis Rush’s opening to his 1958 hit “All Your Love.” Elvin came in with a bass line that was doubled by Buddy’s bass. After a few bars, Teddy launched a cha-cha beat and established a groove.

A flyer a UC Twist Party at Ida Noyes Hall. Author's collectionBloomfield jumped into the tune with a repeated lick reminiscent of Otis Rush’s opening to his 1958 hit “All Your Love.” Elvin came in with a bass line that was doubled by Buddy’s bass. After a few bars, Teddy launched a cha-cha beat and established a groove.

“Daddy’s gettin’ old, baby,” Butterfield said into the mic, naming the tune as the band began to rock. “Gotta go now. It’s bed time!” With that, he sang the first verse.

Daddy’s getting old, baby

Runnin’ all up in years,

Well, daddy’s getting old, baby

Runnin’ all up in years

Well, he ain’t too old, baby,

To change your gears.

The words were a variation on a blues first recorded in 1939 by Bluebird artist Tommy McClennan, one of the musicians that Mike and George Mitchell had discovered living on the South Side earlier in the year. Paul sang the verse with enthusiasm, amusing himself with its double entendre, while Bloomfield peppered the spaces between his phrases. Together they created a tight dialogue between singer and guitar. As Butterfield began his harmonica solo, Teddy Wilson switched the rhythm from his ride cymbal to his snare and punched up the beat. After one chorus, Paul sang two more verses, making reference to a trip to State Street “to buy me a gallon of booze.” He was doubtless thinking about the evening’s activities following the dance.

Then Mike Bloomfield launched his solo.

Once again, the Duo-Sonic’s glassy tone cut through the roar of the band. In the first eight bars, Michael repeated a lick that involved bending a high E up to an F#. In his second twelve, he ripped off a phrase in eighth notes that careened wildly through the changes, eliciting a “Whoa! – he’s good!” from Butterfield. Two more verses from Paul followed and then Michael turned to the rhythm section and brought the tune to a decisive close on a final downbeat.

“Good night, ladies and gentlemen,” Paul intoned into his mic as the dancers slowly cleared the hall. “See you back here next Wednesday night at 10:30. Ha, ha … you may not see me but I’ll see you!”

Norman’s recording, made on a 7-inch reel of Scotch magnetic tape that he’d purchased a few days earlier in a Hyde Park drug store, turned out to be a success. He’d managed to capture the excitement of Butterfield’s sound without the distortion that often marred concert recordings of loud electric bands. And he’d gotten his friend Mike Bloomfield on tape sitting in with the band. He was pleased enough with the results that he later labeled the reel’s storage box “Paul Butterfield & the Buttercups.” It was Dayron’s little joke, but the music he’d recorded was no laughing matter. It was the first recorded instance of the commingling of the talents of Butterfield, Bishop and Bloomfield.

The twist party set that October night was a harbinger of many great things to come.

NOTES

Musical descriptions for theis article come from audio tapes made by Norman Dayron and shared with the author

1. Nick Gravenites interview with Bill Keenom, 1995

2. Norman Dayron, interview with author, 10/28/2011

3. Ibid

4. Mark Naftalin autobiography, sent to Bill Keenom, 1996

5. Norman Dayron, interview with author, 10/28/2011

6. Elvin Bishop, email to the author, 5/21/2015

7 "Fathers and Sons," interview with Paul Butterfield and Muddy Waters; Down Beat, 8/7/1969

CHICAGO CORRESPONDENT

Interviewing Muddy and Wolf

1964 | By David Dann, supplemental to Guitar King: Michael Bloomfield's Life in the Blues

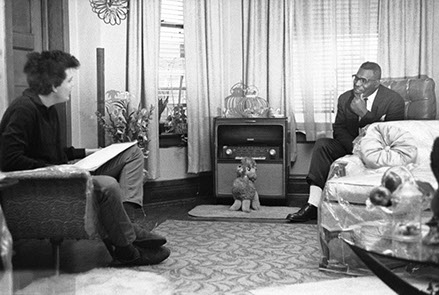

Michael Bloomfield interviews Muddy Waters in Waters' home for Hit Parader on Jan. 9, 1964. Raeburn Flerlage photo-comp.jpg?crc=293763095) In early January 1964, an editor named Jim Delehant contacted Bob Koester. He was looking for someone in Chicago who might be willing to act as a correspondent for one of the music magazines he edited, a monthly called Rhythm & Blues. Koester immediately thought of Michael Bloomfield.

In early January 1964, an editor named Jim Delehant contacted Bob Koester. He was looking for someone in Chicago who might be willing to act as a correspondent for one of the music magazines he edited, a monthly called Rhythm & Blues. Koester immediately thought of Michael Bloomfield.

"He told me about a new band led by Paul Butterfield, and said his guitar player, Mike Bloomfield, knew everybody and jammed with all the blues guys," recalled Delehant. While Michael was more than a year away from joining Paul's band, the two were already being thought of together as representative of Chicago's burgeoning white blues movement. Delehant was intrigued.

"I finally reached Mike and asked him to interview some blues players," said Jim. Bloomfield's characteristic enthusiasm overwhelmed the editor. "He got all excited and couldn’t stop talking about the history every time I spoke with him!" (1)

Delehant worked for the Charlton Publishing Co., located in Derby, Connecticut. He edited its numerous music publications, including its most popular title, Hit Parader. Rhythm & Blues had been launched in 1952 to serve mostly African American readers by covering the popular black music scene. Since becoming its editor in the early 1960s, Delehant had expanded the magazine's coverage to include blues and other traditional black music. He wanted some stories about the great players who were still active in Chicago. Bloomfield said he'd be glad to interview the best of the city's blues masters.

"He did three stories for me that appeared in Rhythm & Blues magazine between 1964 and ’65," Jim said. "The first was with Muddy Waters." (2)

On Thursday afternoon, January 9, Mike Bloomfield and Joel Harlib went down to Muddy Water's brick row house at 4339 South Lake Park Avenue to interview the Chicago blues patriarch. Joining them was Raeburn Flerlage, Midwest wholesale distributor for Folkways Records and a WXFM disc jockey. Ray also took pictures for music publications and record companies, and Delehant had given him the assignment of shooting a few candids to go along with Michael's article.

Michael Bloomfield interviews Howlin' Wolf at home for Hit Parader on Jan. 12, 1964. Raeburn Flerlage photo Waters invited the trio in and ushered them into the house's comfortable front room. They got seated as Raeburn set up his lights, and then Michael began the interview. He questioned the blues man about his birth place in Mississippi, his early days in Chicago, his influences and his favorite blues artists. Joel listened intently while chain-smoking and Flerlage hovered, taking pictures of Muddy from a variety of angles. Midway through the interview, Cookie Cooper, Waters' granddaughter, came in from school. Ray caught several images of the blues legend with his cute granddaughter, knowing the editor would appreciate them. Mike jotted notes down as Muddy answered his questions, and occasional referred to a copy of Samuel Charters' book, "The Country Blues," that he'd brought along to confirm dates and check name spellings. After about an hour, as they were wrapping up, Muddy offered a final prophetic observation.

Waters invited the trio in and ushered them into the house's comfortable front room. They got seated as Raeburn set up his lights, and then Michael began the interview. He questioned the blues man about his birth place in Mississippi, his early days in Chicago, his influences and his favorite blues artists. Joel listened intently while chain-smoking and Flerlage hovered, taking pictures of Muddy from a variety of angles. Midway through the interview, Cookie Cooper, Waters' granddaughter, came in from school. Ray caught several images of the blues legend with his cute granddaughter, knowing the editor would appreciate them. Mike jotted notes down as Muddy answered his questions, and occasional referred to a copy of Samuel Charters' book, "The Country Blues," that he'd brought along to confirm dates and check name spellings. After about an hour, as they were wrapping up, Muddy offered a final prophetic observation.

"I have a funny feeling. I have a feeling a white is going to get it and really put over the blues," said the 48-year-old blues star. He thought for a moment, and then added, "I'm sure they'll start singing the blues. But I don't know whether they can deliver the message. I know they can feel it, but I don't know if they can deliver it." (3)

If Muddy Waters was thinking of Mike Bloomfield when he made his prediction, he didn't say. But he could easily have had Michael in mind and, for many − including Muddy himself − the guitar wiz from Glencoe would indeed deliver.

For the moment, though, Michael had an interview to deliver. He quickly wrote a three-page story based on his notes and sent it off to Jim Delehant. The editor could see right away that while his new Chicago stringer had gotten the facts concerning Muddy Waters' career, the piece still needed quite a bit of fleshing out. He worked with Bloomfield over the next few months to expand the interview and, by the time it was published in July, it was an informative and insightful read.

The following week Bloomfield did a second interview for Rhythm & Blues, this time with Howlin' Wolf. He and Ray Flerlage visited Wolf in his West Side home on January 12. Delehant had tactfully suggested that Ray and Michael write the piece together, so while the guitarist asked questions and took notes, Flerlage shot photos and listened carefully. In a few days, Bloomfield worked up another three-page story, one more detailed than his Waters interview, and sent it off to the editor. Flerlage did likewise, and Delehant combined the two stories, merging Mike's just-the-facts text with the photographer's more florid prose. When the piece appeared in February 1965, it was the most in-depth interview with Howlin' Wolf yet published. The Memphis blues giant came off as intelligent, insightful and appreciative of many of his contemporaries. Rhythm & Blues gave Flerlage the lead byline and voiced the interview from his point of view. It relegated Bloomfield's contribution to a half-dozen reworked paragraphs.

A month later, on February 8, Bloomfield participated in a third interview for the magazine, this time with Ray Flerlage and his friend, Down Beat editor Pete Welding. Guitarist and singer John Lee Hooker was the subject, and Welding taped the conversation with him in Hooker's South Side hotel room. He and Michael asked the questions, while Ray again took photos. Freed from having to take notes by the recording, Bloomfield strummed Hooker's big Epiphone guitar and even got a few pointers from the Detroit bluesman. When the interview was published in Rhythm & Blues in the winter of 1964, it carried Pete Welding's byline but also credited Bloomfield and Flerlage. Pete was a professional journalist and knew his craft, and the magazine's editor very much appreciated that.

But it was Mike Bloomfield who had really impressed Jim Delehant.

"I just liked his mind − the way he thought about music," said the editor. He would make a point of following the young guitarist's career. (4)

NOTES

1. Jim Delahant, email to the author, 6/30/2013

2. Ibid

3. "An Interview with Muddy Waters," Michael Bloomfield; Rhythm and Blues, July 1964

4. Jim Delahant, email to the author, 6/30/2013

BONUS PAGES back to top

MICHAEL BLOOMFIELD | AN AMERICAN GUITARIST

CONTACT | ©2019 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED